There are many causes of scoliosis ranging from neuromuscular to degenerative, but the most common type of scoliosis is adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, diagnosed between the ages of 10 and when growth is done. Idiopathic scoliosis, which accounts for 80 percent of known diagnosed cases of childhood scoliosis, is not clearly associated with a single causative source. Regardless of what causes scoliosis, the most important decision is what action to take to address the curving spine.

Scoliosis isn’t something a person can catch; it’s a structural spinal condition with different forms/causative sources. The most prevalent condition type is classified as idiopathic, meaning unknown causation, and other less-typical forms have neuromuscular, congenital, degenerative, and traumatic causes.

Scoliosis can be a complex condition to treat, partially because it develops across such a wide severity spectrum of mild to severe, in a wide variety of curve patterns, differing patient ages, and different abilities to perform exercises, and also because there are multiple causes.

When scoliosis is first diagnosed, part of the diagnostic process is classifying the condition based on important patient and condition characteristics.

Remember that scoliosis is not primarily a structural spinal condition, meaning that it’s due to underlying neurologic causes that only manifests in the spine itself.

The unnatural sideways spinal curve that develops, in idiopathic scoliosis, also has a rotational component, meaning it doesn’t just bend to the side, but always has a twisting of the spinal bones, making it a 3-dimensional condition.

To be formally diagnosed as scoliosis, an unnatural spinal curve has to have a minimum Cobb angle measurement of 10 degrees, and once these parameters have been met, a diagnosis of scoliosis is given, and the condition must be comprehensively assessed by a careful history, physical examination, and X-rays.

In addition to patient age, curvature location, and condition severity, causation is a defining variable that further classifies conditions by type: idiopathic, degenerative, neuromuscular, congenital, or traumatic.

Another key condition characteristic is the progressive nature of scoliosis.

Now that we’ve touched on the different condition types and their progressive nature, let’s explore the underlying causes of these different forms, starting with the most prevalent: idiopathic scoliosis.

Idiopathic conditions aren’t clearly associated with a single causative source, but this is not the same as having no causative source; instead, idiopathic scoliosis is considered to be multifactorial, meaning caused by different variables that can vary from person to person.

As mentioned, 80 percent of childhood scoliosis cases are idiopathic, including the most prevalent type, adolescent idiopathic scoliosis; the most common types of scoliosis in adults are adolescent scoliosis in the adult (ASA), along with de novo (degenerative) scoliosis.

As explained, both childhood and adult scoliosis is progressive, and while we don’t fully understand its etiology, we do understand its main triggers for progression: growth in childhood, and degenerative changes to the spine in adults.

In AIS, due to the stage of growth and development adolescents are in, marked by rapid and unpredictable growth spurts, they are at risk for rapid-phase progression, which is why proactive treatment started as close to the time of diagnosis as possible can be so beneficial.

All large curves started out as small curves, and it is very important to begin treatment when the curve is as small as practical, which is at the time of diagnosis!

What we also know about adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) is that it’s more commonly diagnosed in females, who are also more likely to experience significant progression; this is because girls start their growth spurts when they are younger, and the postural control mechanisms are not fully formed.

While scoliosis is more common in children and adolescents, it also affects adults in two main types: idiopathic and degenerative.

What Causes Scoliosis in Adults?

Cases of idiopathic scoliosis in adults are either previously-treated cases of AIS, or many times, cases that went undiagnosed and untreated in adolescence, progressing with growth and maturity into adulthood; all children with scoliosis that is not completely resolved by treatment become adults with adolescent scoliosis.

While it might seem difficult to imagine how a person could live with scoliosis for so many years unaware, the condition isn’t commonly painful in children and adolescents, therefore early detection can be a challenge.

Once scoliosis becomes a compressive condition in adulthood, the compression of the spine and its surrounding muscles and nerves can cause varying levels of pain, but that compression is absent in younger patients who have yet to reach skeletal maturity; pain is the number one reason adults come to me for a diagnosis and treatment.

In addition, particularly in mild forms, AIS isn’t known to cause noticeable functional deficits, and related postural changes can be subtle and difficult for anyone, other than an expert trained in what to look for, to notice.

The unfortunate reality is had these adult patients been diagnosed and treated in adolescence, their spines would likely be in far better shape than they are by the time they reach a diagnosis in adulthood.

The prevalence of idiopathic scoliosis in adults shows how important it is to be aware of the condition’s early signs so early detection is possible, as is applying proactive treatment to manage the condition’s progressive nature, before significant progression has already occurred.

The next most prevalent form of scoliosis to affect adults is degenerative, and various studies show that 30 to 60 percent of adults over the age of 65 have a diagnosable scoliosis; it is very common!

Degenerative scoliosis, also known as de novo scoliosis, is caused by degenerative changes in the spine.

Natural spinal degeneration can be part of aging and is most common after the age of 40, but it can also be related to the cumulative effect of certain lifestyle choices.

The very design of the spine is based on movement, so leading a sedentary lifestyle can speed up spinal degeneration, rather than staying active so the spine and its surrounding muscles are kept as strong and loose as possible.

Carrying excess weight also puts more pressure on the joints of the body, including the spine, and can lead to increased wear over the years.

Chronic poor posture can slowly affect the spine’s function and disrupt its biomechanics, not to mention making it harder for the spine and its surrounding muscles to maintain its natural and healthy curves.

Those with occupations that involve repeatedly lifting heavy objects need to be educated on the ergonomics of proper lifting, to help ensure no one section of the spine is exposed to uneven wear and at risk of injury.

Most commonly, the first parts of the spine to show deterioration are the intervertebral discs.

The discs sit between adjacent vertebrae (bones of the spine), and once they start to degenerate, they can change shape and become desiccated, bulging, or herniated.

In addition, healthy intervertebral discs are needed to preserve spinal health and function by providing cushioning, spinal flexibility, structure, and as the vertebrae attach to the discs, if a disc’s shape changes, this can alter the position of adjacent vertebrae and lead to the development of an unnatural scoliotic curve.

There are also instances where scoliosis develops as a secondary complication of another condition.

Neuromuscular scoliosis (NMS) is considered an atypical form because there is another force behind its development.

In NMS, scoliosis develops as a secondary complication of a neuromuscular condition/disease such as cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, and spina bifida, to name a few.

Neuromuscular scoliosis involves a disconnect in brain-body communication, disrupting the ability of muscles/connective tissues to support the spine, and if combined with the use of a wheelchair, the slouching posture almost always facilitates the development of scoliosis.

While not everyone with a neuromuscular condition will develop scoliosis, it is a common complication, and NMS severity depends largely on the extent of nerve and muscle involvement.

The next form of scoliosis with known causation is when infants are born with.

Congenital scoliosis is another atypical form, affecting approximately 1 in 10,000.

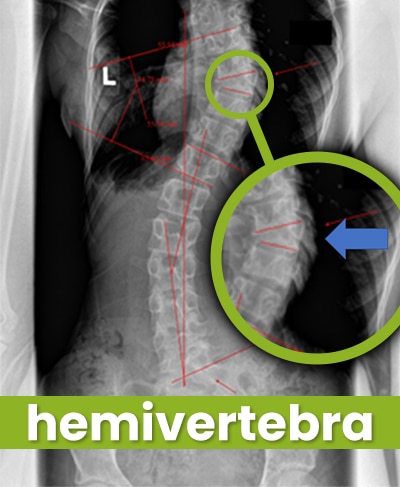

Congenital scoliosis is caused by a malformation within the spine itself (structural abnormality) that develops as the spine is forming in utero.

Scoliosis can also be caused by a significant spinal injury.

In traumatic scoliosis, the spine’s ability to maintain its natural curvatures and alignment is compromised because of a trauma sustained by the spine.

Traumas include fractures and breaks due to injuries caused by car accidents, falls, etc.

In addition, the presence of tumors pressing on the spine, and the uneven pressure, can force a spine out of alignment and an unnatural curve to develop.

Now that we’ve discussed the main forms of scoliosis, both with unknown and known causes, let’s address a common causation-related question:

“Is Idiopathic Scoliosis Genetic?”

While a debate that continues to circle around idiopathic scoliosis is whether or not it’s caused by genetics, the general consensus amongst experts is that scoliosis is more accurately deemed familial than genetic.

Despite years of research, a specific gene, or genetic mutation, has yet to be discovered that clearly accounts for the condition’s development, and families also share a lot more than just their genes.

A condition classified as familial means that while a person is more likely to develop it if someone else in the family has been diagnosed, this could be related to one of multiple shared factors, or a combination of them: geography, socioeconomics, lifestyle, posture, diet, weight, growth patterns, and even common responses to stress.

As you might recall, idiopathic scoliosis is commonly regarded as multifactorial, and in light of the many different shared factors within a family, this could be a potential explanation as to why scoliosis is more prevalent within a family, if not clearly attributed to genetics.

So to clearly answer the related questions of what causes scoliosis and how do you get scoliosis, the answer will vary based on the condition type in question.

In the vast majority of known diagnosed scoliosis cases (80 percent), they are not clearly associated with a single causative source, and the remaining 20 percent consists of atypical types with clear causative sources: degenerative, neuromuscular, congenital, and traumatic.

As a CLEAR-certified scoliosis chiropractor, I believe in the merits of proactive treatment applied as close to the time of diagnosis as possible.

While there are no treatment guarantees, early detection does increase the chances of treatment success, but only if a diagnosis is responded to with proactive treatment.

Integrating different forms of treatment such as chiropractic care, a variety of individually designed in-office therapies, custom-prescribed condition-specific home exercises, and if necessary, corrective bracing can facilitate the design of customized treatment plans: something the complex nature of scoliosis necessitates.

So keep in mind, while we don’t always know what causes scoliosis, we do understand how to manage its progressive nature and prevent increasing condition severity with proactive treatment.

CLEAR provides a unique and innovative way of understanding scoliosis. Sign up to receive facts and information you won’t find anywhere else.